Previous studies of gender in political advertising indicate strong similarities between the self-presentations of male and female candidates in ads (Sapiro, Walsh, Strach & Hennings, 2011). Because past studies have focused only on federal government races, we aim to update these findings with data on advertising in down ballot races in addition to federal races. We also use data from 2012 and 2016 in order to examine a potential change over time with respect to gender differences.

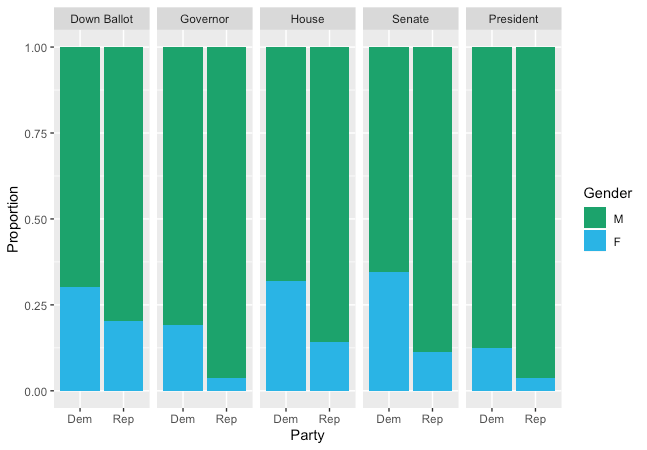

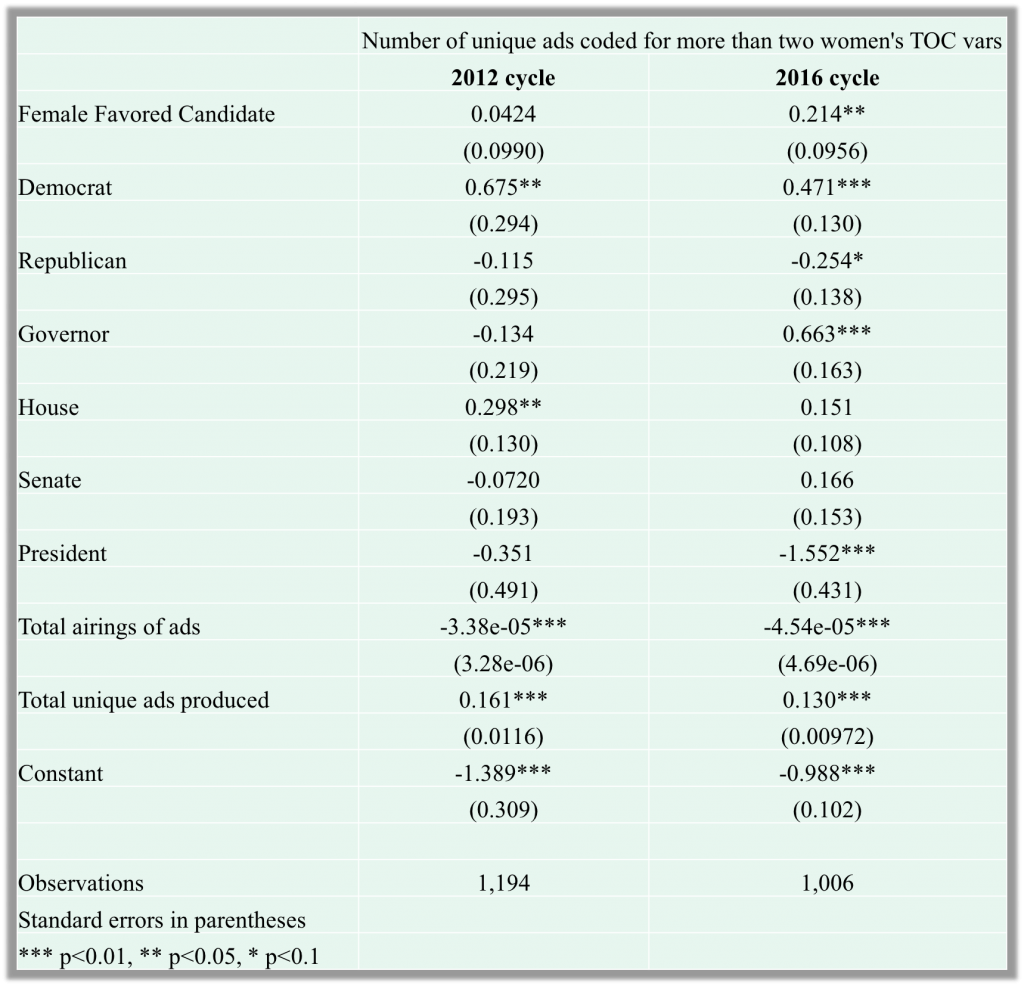

Herrnson, Lay & Stokes (2003) and Schaffner (2005) suggest that campaigns may focus on women’s issues in order to increase votes. We examine ads produced by candidates to find potential gender differences in strategic mentions of women’s issues by the candidates themselves. Hayes (2005) suggests that party affiliation could also affect the presentation of a candidate in an ad, due to public opinion on qualities associated with candidates of either party, which we account for in our model. We include all candidate-sponsored ads from 2012 and 2016 that feature a favored candidate with an ascertainable gender. This is limited to ads aired in races for three down ballot seats (Attorney General, State Representative, and State Senate) as well as races for Governor, House, Senate, and President. This includes 4,245,001 airings of 8,802 unique ads aired by 2,200 candidates.

Figure 1: Gender of candidates by party and level of office

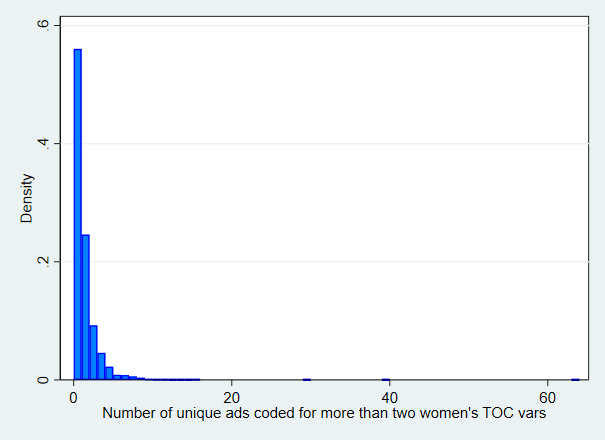

We examine a set of coded mentions of women’s political issues that we classified using a combination of stereotype literature, legislation data, and public opinion survey data. Because there is no single reliable method of categorizing a political issue based on association with gender, we carefully examined each of these sources in analyzing the WMP issue battery to identify 58 Table of Contents (TOC) broad mention variables that correspond to mentions of women’s issues. For each candidate, we find the total number of unique ads that are coded for two or more of these variables, as well as the total number of airings for these ads.

We examine a set of coded mentions of women’s political issues that we classified using a combination of stereotype literature, legislation data, and public opinion survey data. Because there is no single reliable method of categorizing a political issue based on association with gender, we carefully examined each of these sources in analyzing the WMP issue battery to identify 58 Table of Contents (TOC) broad mention variables that correspond to mentions of women’s issues. For each candidate, we find the total number of unique ads that are coded for two or more of these variables, as well as the total number of airings for these ads.

Figure 2: Distribution of dependent variable

We find that for the 2016 cycle the gender of the candidate is significantly associated with the number of unique ads produced that mention two or more women’s TOC variables. However, no significant relationship is found for the 2012 cycle. Additionally, no significant relationship is found for either cycle at the airings level. These findings suggest that female candidates may have begun discussing women’s issues more in their campaigns during a year featuring a woman at the top of the ballot.

Table 1: Regression output

While our results indicate a potential relationship between gender and discussion of women’s issues in political ads, there are several notable limitations to our model. We are unable to account for competitiveness of down ballot races due to lack of data, yet this would potentially have a strong impact on the number of ads produced and aired in a given race. Additionally, we are unable to separate ads aired in primary races from ads aired in general races. These two categories of races could potentially exhibit different ad production and airing behaviors.

Some of the TOC variables may refer to different policies within the same general women’s issue. Further classification work could group them differently to account for potential redundancy and provide a more accurate measure of distinct issue mentions.

References

Hayes, D. (2005). Candidate qualities through a partisan lens: A theory of trait ownership.

American Journal of Political Science, 49, 908–923.

Herrnson, P. S., Lay, C., & Stokes, A. K. (2003). Women running “as women”: Candidate gender, campaign issues, and voter-targeting strategies. Journal of Politics, 65, 244–255.

Sapiro, V., Walsh, K. C., Strach, P., & Hennings, V. (2011). Gender, context, and television advertising: A comprehensive analysis of 2000 and 2002 House races. Political Research Quarterly, 64, 107–119.

Schaffner, B. F. (2005). Priming gender: Campaigning on women’s issues in U.S. Senate elections. American Journal of Political Science, 49, 803–817.