By Efi Miller ’25, Jasmine Sanchez, and Jack Trowbridge ’25

Introduction

In recent years, as political polarization has increased throughout the American public, two topics that have seemingly gained increasing attention are race and gender. From discussions around Black Lives Matter to immigration policy to abortion and beyond, identity politics have gained attention in political campaigns and among the public. A September 2022 Gallup survey shows that race relations/racism, abortion, and immigration were named as one of the most important problems faced by the country after the economy. Given the relevance of these issues, our group decided to conduct an analysis of how these topics are discussed in the 2022 political ads. The aims of this analysis are twofold. First, we seek to provide a big picture of how politicians discussed topics relating to race by focusing on Critical Race Theory (CRT). Second, we want to analyze whether they used these issue mentions to bolster their own platforms or to attack opposing candidates.

Methods

Although CRT was a hot topic leading into the 2022 election cycle, it did not receive much attention in political ads relative to other issues. Using a dataset produced by the Wesleyan Media Project (WMP), we examined 78 unique television ads that WMP coders identified as mentioning CRT, all of which were supported Republicans. These ads were aired across the U.S. House, U.S. Senate, or gubernatorial races and accounted for more than 30,000 airings between April 12 and October 30, 2022. The ads were aired across multiple election levels, including primaries, runoffs, and general election races.

To explore how ad tones differed across the ad airings in our dataset, we used the following variables:

- State: U.S. state where the ad’s election took place (regardless of election type)

- Election Type: U.S. House, U.S. Senate, or Governor

- Election Level: Primary, Runoff (post-primary), or General election.

- Tone: positive (supporting a candidate), negative (attacking a candidate), or contrast (supporting a candidate and attacking another candidate)

Content Analysis

To complement our quantitative analysis of CRT, we conducted qualitative content analysis to further explore how CRT and other identity politics topics were discussed in the 2022 political ads. We developed a Qualtrics coding instrument to track elements about the ads’ appearance, tone, and word choice. We then conducted several practice rounds, revising our questions as necessary based on team discussion. After several rounds of revisions, we finalized our coding instrument (codebook) and began live coding. Our team ultimately coded a random sample of 157 ads that aired during the general election period.

Results

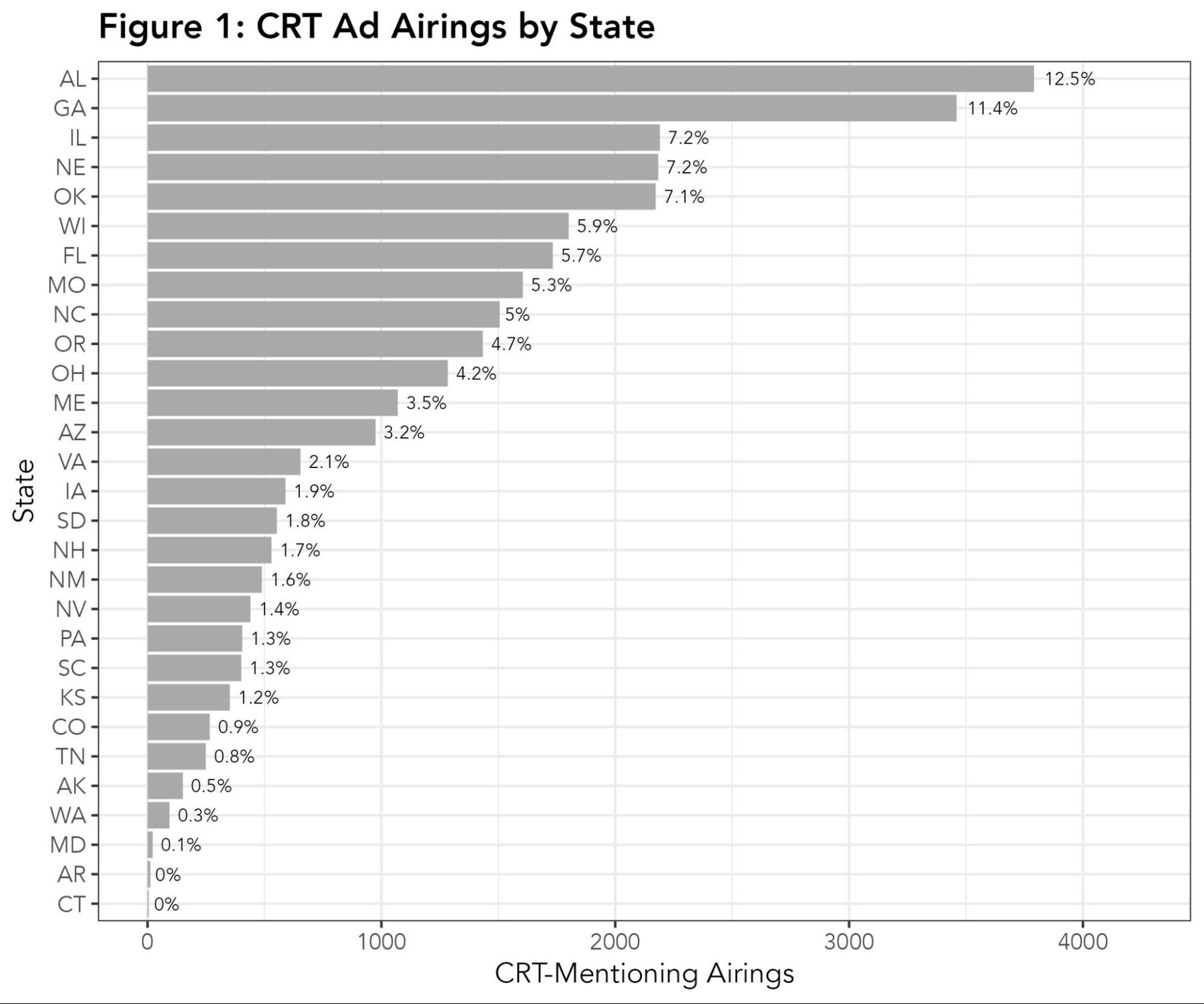

Ads mentioning CRT were aired most frequently in red states, as shown in Figure 1. Alabama and Georgia—the top two states, respectively—together account for more than 7,000 airings (24% of all airings), with the three next-highest states—Illinois, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. The ads aired in Illinois, a historically blue state, were funded by conservative candidates and PACs that supported the Republican Party.

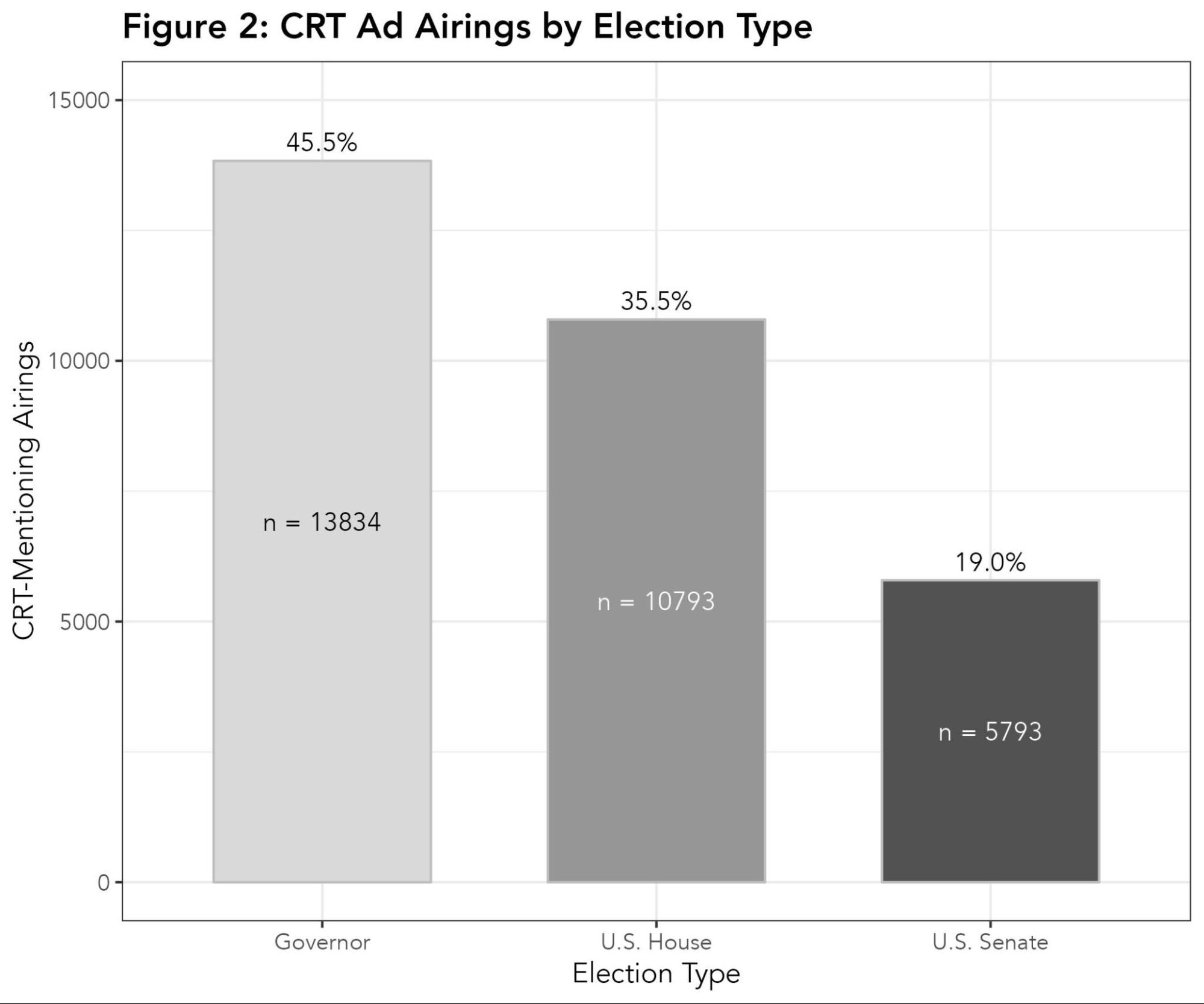

Most ads mentioning CRT were aired most often in gubernatorial races, representing 45% of all airings; U.S. House races accounted for 35% of airings, and U.S. Senate races represented 19% of airings, as shown in Figure 2.

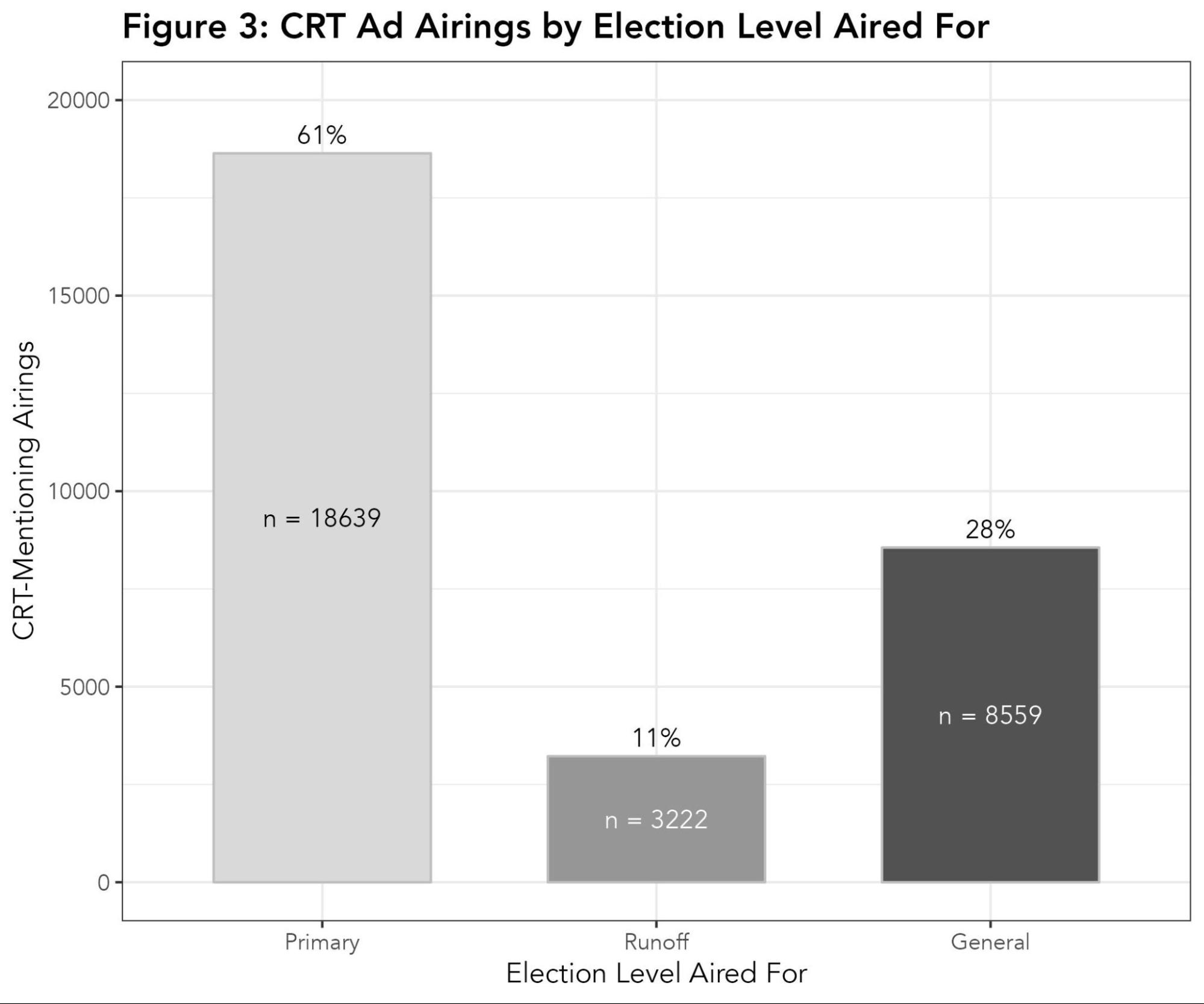

We also found a substantial variation in airings across election levels, as described in Figure 3. The airings from primary elections dominated over other levels, representing 61% of all ad airings. General election races represented 28% of all airings, and post-primary runoff races represented 11% of all airings.

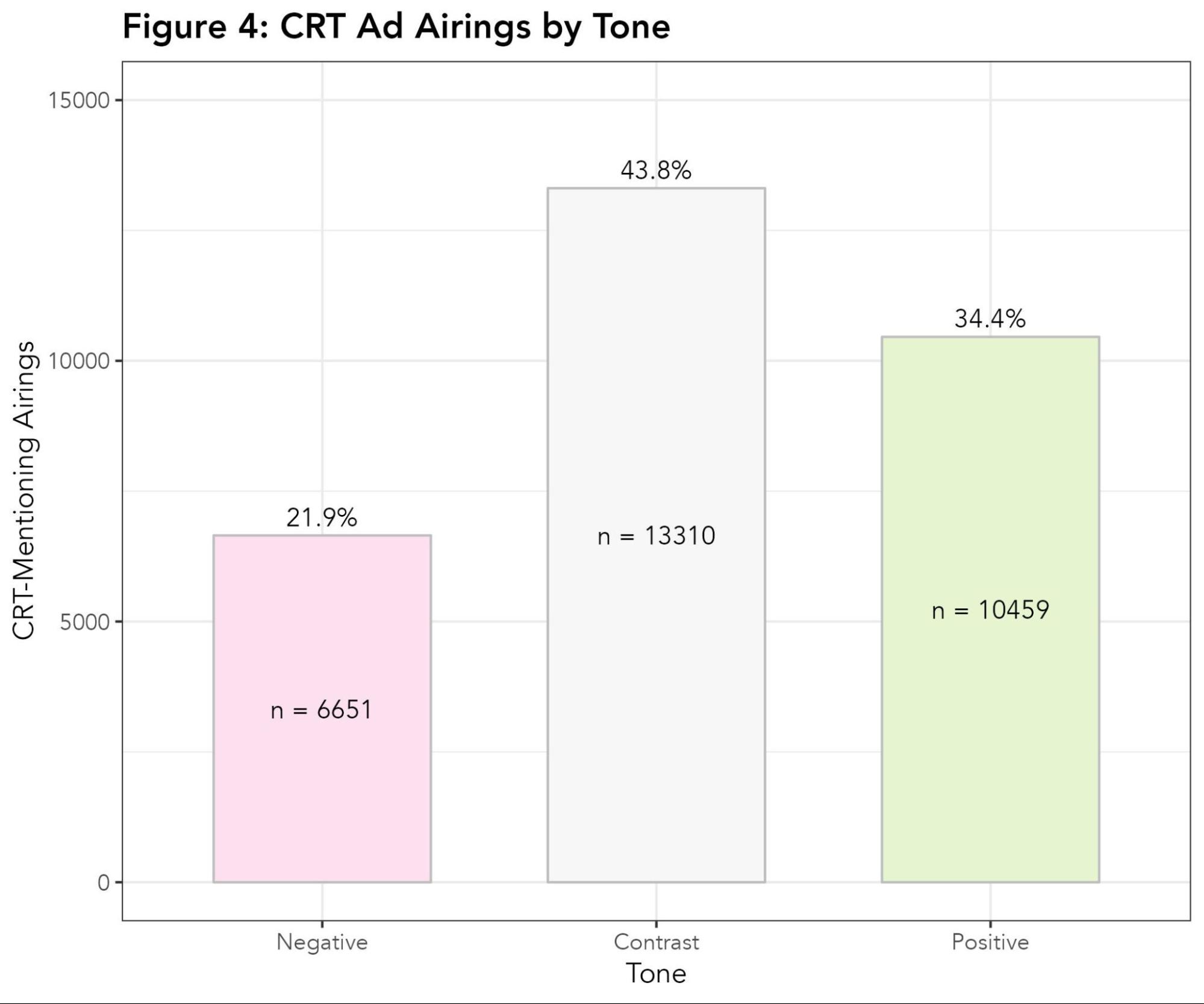

Across all election types and levels, 44% of CRT-mentioning ad airings were coded with a “contrast” tone, followed by 34% of airings being “positive” and 22% “negative,” as depicted in Figure 4. While these results indicate that a plurality of ad airings both praised a candidate and attacked an opponent, it is important to notice the need to distinguish between an ad’s tone toward candidates and its tone toward CRT. Here, we are examining the ad’s tone toward candidates, not the ad’s tone toward CRT. In other words, an ad coded as “positive” does not indicate that the ad promotes CRT but rather promotes a candidate while mentioning CRT.

Content Analysis

Figure 5: Screenshots from television advertising mentioning Critical Race Theory

Sponsored by Republican Kay Ivey (top left), American Jobs and Growth Fund (top right), Republican Leora Levy (bottom left), School Freedom Fund (bottom right).

When limiting the WMP dataset to ads that mentioned CRT, we were left with a relatively small number of ads, so we expanded our analysis to include ads with other race-related issues (eg. Civil Rights/Racial Discrimination, Crime, Incarceration/Sentencing, Protests/Riots, Immigration, DACA/Dreamers, Capital Punishment, and Police Brutality/Racial Violence). For comparison purposes, we also added gender issues such as Women’s Health, LGBTQ Issues/Rights, and Gender Discrimination (not LGBTQ). The resulting dataset included 1,500 creatives from the 2022 U.S. House, Senate, and gubernatorial races. The initial analysis of the subset of 157 ads we coded revealed that ads were more likely to attack people or policies, as expected. While we coded 123 ads as attacking people or policies, only 72 supported people or policies. We also considered visual effects used in ads and found that 96 ads used dark colors and tones, 91 ads used bright colors and tones, and 41 ads included both of these visual effects.

While all of the ads in our sample were coded by WMP as containing a race or gender mention, only two of the ads in our set contained an explicit mention of CRT. In addition to CRT, we coded our sample for mentions of police brutality, crime, protests, incarceration, gender issues (non-LGBTQ), LGBTQ issues, and immigration. The most common issue mentioned was crime, which was mentioned in 77 ads. The next most common issue mentioned was immigration, which was mentioned in 42 ads.

Conclusion

There are a few key findings from our exploratory data analysis. Firstly, most of the CRT ads were aired in red states by conservative candidates. One of the exceptions is Illinois, a historically blue state, which was ranked in the top three states with the most CRT ads aired during this period. As previously mentioned, these ads were funded by conservative candidates and PACs that supported the Republican Party. Second, gubernatorial races and primary elections accounted for most of the airings mentioning CRT. Third, most of the ad airings mentioning CRT were coded with a contrasting tone. While these results suggest that many ad airings both praised one candidate and attacked another, it is important to note that this only reflects the ad’s tone toward the candidates, not the tone toward CRT. Fourth, our content analysis reveals that these ads were more likely to attack people or policies. We also found that most of these ads used dark colors and tones.

For future analysis of CRT or other race-related issues in TV ads, we would like to expand our content analysis to include a larger sample of ads. CRT is only one of many social identity and education issues mentioned in campaign ads, with others including school choice, the Black Lives Matter protests from 2020 onwards, and others. Further research to explore the overlap between CRT and other issues mentioned within the same ads is needed. Additionally, although our full dataset had over 30,000 airings, CRT was still a relatively “niche” issue in the 2022 elections, when issues of crime, abortion, taxation, and inflation dominated (Stevens & Itkowitz 2022). Finally, researchers might want to explore the factors that explain why some candidates focus more on this subject than others. For example, does an incumbent running for a seat affect the number of ads or volume of airings mentioning CRT? Questions such as these could lead to fruitful insights on a novel topic in America’s political and cultural conversations on identity politics.