According to the NYT and several other news outlets, as the election neared, polling in battleground states like Texas and Florida indicated that Biden was not leading Trump with the Latino vote in every case. And even in the cases when he did hold a lead, it was by a much smaller margin than Clinton did against Trump in 2016.

This was significant because as the Latino electorate has grown in the US, especially in key battleground states, both parties have been eager to target Latino voters in their ads to garner their support. I wanted to conduct research this semester that would allow me to dig into these ads for the presidential race. While this could include a variety of different methods, I chose to investigate how each candidate might be targeting Latino voters through Facebook advertising in Spanish.

Data used in this analysis came directly from the Wesleyan Media Project, which tracks advertising through Facebook’s Ad Library API tool and Ad Library Report.

Methods

This semester I conducted my research in two parts. When I began the project, I used the date range of September 1st to October 15th. Data was pulled from the Wesleyan Media Project server and filtered for advertisements released by the Biden and Trump campaigns. This would capture spending before and after the polls were released. As the semester progressed, I expanded the date range to include ads released up until election day.

My next step was developing a list of keywords that would return all ads in the dataset in Spanish that were about voting. My list of keywords was: vota, por, votar, and para. These words translate to English as “vote” and “for”.

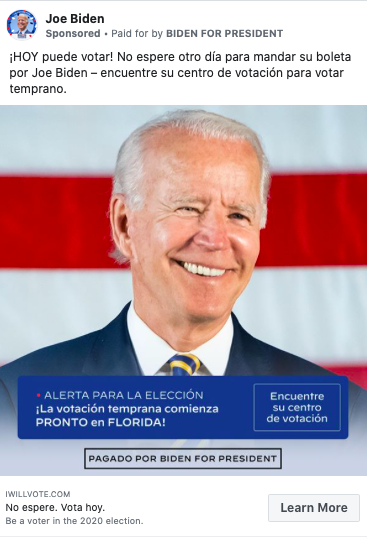

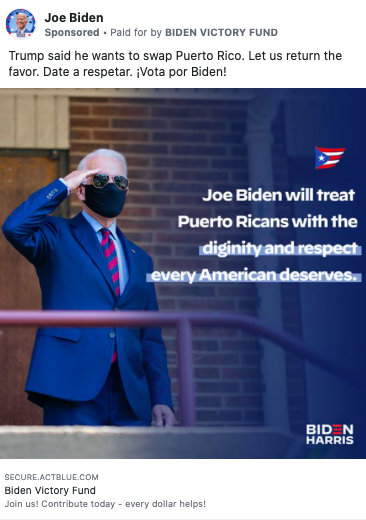

These keywords were selected by going through Biden and Trump’s ad library on Facebook and looking for the most common words in the ads that were in Spanish. I determined that the phrase “Hoy puede votar” (today you can vote) or “Sacrificamos mucho para ser libres y respetados” (we sacrificed a lot to be free) were some of the most common in Spanish language ads (as shown in Figure 1 and 2). These keywords were unlikely to return false positives because if the Spanish word appeared in the ad, then it was probable that at least part of the ad was in Spanish.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Lastly, to determine how much each candidate spent, I used Facebook’s estimates of the upper and lower bounds of spending and conducted an average of those two numbers.

However, throughout the semester, it became more apparent that this method was not capturing the complete picture. Ads that didn’t use these keywords, but were in Spanish, would not be picked up. An ad released by Latinos for Trump, as shown in Figure 3, is an example of this.

Figure 3

Thus, after Election Day, I expanded my date range through November 3rd and used another method to identify Spanish ads.

With the expanded data set, I used the “Detect Language” feature in Google Sheets to identify ads that had text in Spanish, and I ran the same keyword search for comparison. I imported the data sets from the WMP server into Google Sheets and then selected only the ad rows that the feature had marked as “es” (an abbreviation for español or Spanish).

Results

The results for my first keyword search using the data from September 1st to October 15th showed that Biden spent approximately 61,765 dollars on Spanish Language ads. Trump outspent Biden by spending approximately 103,336 dollars on Spanish Language ads during this time period.

When I updated my dataset to include ads released until November 3rd, Trump’s lead no longer held. The keyword search on the expanded date range showed Biden spent approximately 469,450 dollars on Spanish ads while Trump’s spending remained the same at approximately 103,336 dollars. In other words, Trump’s spending on Spanish ads stopped after October 15th. As the election neared, Biden ramped up spending and outspent Trump on Spanish Language ads.

The results from the detect the language feature validate this conclusion; yet, the numbers were slightly different. This analysis showed Biden spent approximately 449,250 dollars on Spanish Language ads (about 20,000 dollars less than the keyword search). And it reported Trump’s spending at 198,000 dollars (about 95,000 dollars more than the keyword search).

Since this feature was meant to catch ads that keyword searching may have missed, I expected both the results to be larger. Therefore, the result for Biden puzzled me. However, the answer lies in the types of ads that Biden released during this time period.

I applied the “detect language” feature to the subset of ads that the keyword search had identified to see what language they were marked as. I realized that Biden released ads in English, but added a phrase in Spanish at the end (as shown in Figure 4). These ads were then counted by the keyword search, but they were marked as English by the feature, so they were not computed into the total average.

Figure 4

In order to get a more accurate number, I combined both datasets to include ads that were counted by the detect the language feature or counted by the keyword search. The results by candidate are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1: Results of Approximate Spend By Candidate and Method

| Candidate | Detect the Language Feature | Keyword Search | Combined Results |

| Biden | $449,250 | $469,450 | $491,500 |

| Trump | $198,000 | $103,336 | $198,050 |

Conclusion

The results of my analysis were pretty surprising because it was very difficult to find a method that alone would capture all the ads in Spanish. However, by combining both methods used in this report, I was able to generate a more accurate result of the total spend on Spanish language ads by both candidates during the campaigns.

Biden exceeded Trump’s spending on Spanish language ads by 2.5 times, but this happened as the election neared when he ramped up spending as Trump stopped spending on Spanish.

This analysis highlights the faults of using automated methods to code language ads. Both methods miss ads because of the keywords used or the amount of Spanish in the ad. Going forward, I would like to expand on this research by exploring other methods of detecting language like using Google’s Compact Language Detector Package in R.